Their hole, named Hole U1601C, extended a record 1,268 meters, and what the researchers extracted was even better. They managed to recover a whopping 71 percent of the core sample.

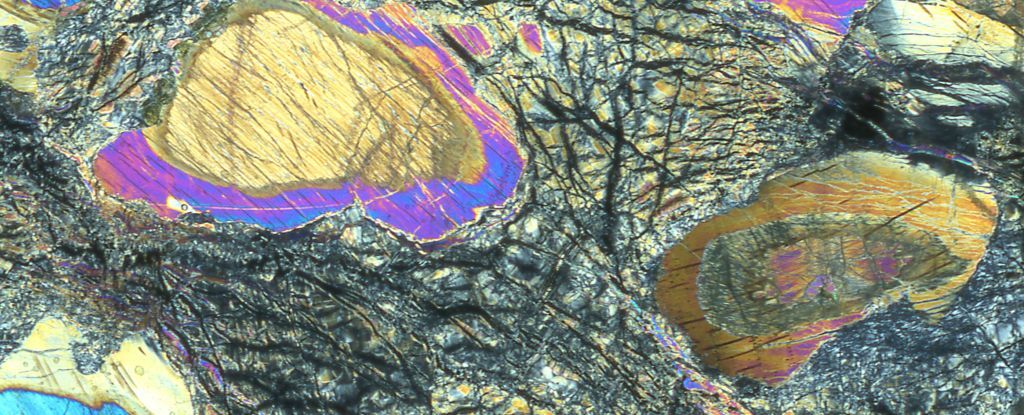

This sample, like the massif itself, consists of peridotite, a coarse-grained igneous rock made up almost entirely of olivine and pyroxene.

When seawater is introduced, its meeting with the minerals provokes a reaction known as serpentinization, transforming the exposed olivine and pyroxene into serpentine minerals, producing hydrocarbons that can be used by seafloor lifeforms. But the result for geologists is that it becomes harder to interpret the rock, like trying to read ink that has been left in the rain.

Interestingly, the researchers found that their core sample had become highly serpentinized, with even the least-altered peridotite being at 40 percent transformed, for the entire length of the sample, suggesting that seawater penetration is pretty high. In spite of this, though, the primary rock composition was preserved better than shallower cores, revealing new information about the mantle beneath the Atlantis Massif.